What is ‘positionality’ and why is it important in water management?

Written by Lucy Stuart, Kate McKenna and Isobel Bender

Written by Lucy Stuart, Kate McKenna and Isobel Bender

Travelling through the Pilbara, WA. Photo credit: Siwan Lovett

In this article we refer to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples as Indigenous Peoples and Indigenous Nations. We acknowledge that other terms such as First Nations, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, and First Peoples can also be used.

As individuals, we hold opinions and biases that are related to our upbringing, beliefs, experiences and environment. These relate to gender, race, age, societal contexts and more — whether they are negative or positive, conscious or unconscious — they affect how we make sense of the world around us and how we act in day-to-day life.

Positionality is a tool that can help us think about this phenomenon, crucially it is a way to ‘own’ our personal perspectives in relation to Indigenous Peoples. Within this article, we are exploring this in the context of working in the natural resources management sector. It is important to note, however, that this concept can be applied to all other aspects of life. Our hope is that this provides an opportunity to reflect on your own views and stories, helping map a pathway to more effective engagement with Indigenous Peoples.

In this article we – Lucy, Kate and Izzy – reflect on our position as non-Indigenous people working in the environmental space, where we work on Country with deep connections to Indigenous Peoples. It is not our intention and nor do we wish to speak on behalf of Indigenous Peoples, rather, we hope to centre Indigenous concepts in the environmental space by recognising that we work within a multitude of cultural and social values. We feel that it is crucial all of us are aware of our own inherent biases that we bring as non-Indigenous peoples. so that we may be better allies (Snow, 2018). Allies is used in this context to signify a non-Indigenous person working with Indigenous communities in a meaningful and respectful way.

At the ARRC, we work within the natural environment as part of our Rivers of Carbon and regional projects, moving through Indigenous Nations landscapes and waterways, and step[ing into a myriad of historical and current contexts that transcend our work. As a non-Indigenous organisation, we try to recognise that our position is one of power and privilege. We have the potential to influence the water science discourse so that it better aligns with our own perspectives. Sometimes we may do this unintentionally, at the expense of Indigenous Peoples’ perspectives. We believe that we must recognise our power and position, otherwise we risk acting as bystanders to the continuing colonisation* of Australia.

* An important concept to understand is that colonisation is not an isolated event that occurred 200 years ago. Colonisation has been described as a ‘system’ or an ‘ongoing event,’ where the way our society operates unconsciously/consciously benefits those who are non-Indigenous at the detriment and continuing erasure of Indigenous Peoples.

To foster this recognition, we explore the notion of positionality within the ARRC, and discuss its role/place for our work, and for all those involved in natural resources management.

Within the Australian Indigenous Studies discourse, positionality can be thought of as a map to help us to understand our ways of knowing, our ways of being and how we relate to those around us. An excellent resource is the Identity Map developed by Department of Education and Training staff, James Cook University’s School of Indigenous Studies and the Western New South Wales Regional Aboriginal Education Team between 2007 and 2009. It has a list of helpful guiding questions that can help you to explore your positionality. In this resource, they state:

‘It has been found that (you) cannot effectively engage with Aboriginal perspectives and Aboriginal knowledge unless they are first strongly grounded in a critically self-reflective knowledge of (your) own cultural standpoint.’

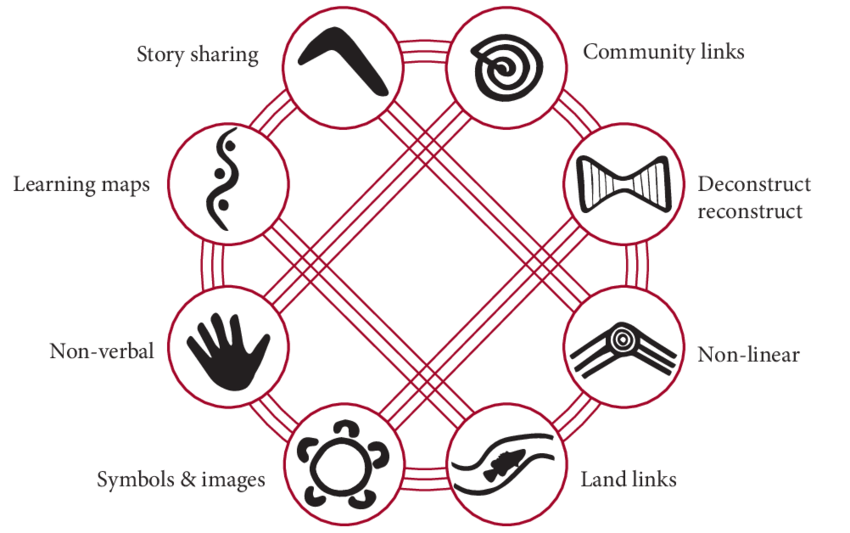

The diagram below depicts how these experiences are vital for positionality, along with the numerous relationships we have as part of our lives. The diagram is called ‘8ways’ and is known as a pedagogy framework, providing a means of cultural interface between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

There are several other definitions or understandings of positionality.

Using a socio-cultural perspective, Feminist theorist Diane Wolf (1996) discusses positionality in the context of power, where your power can shift depending on whether you are an outsider, insider-outside or outsider within. For example, when considering the position of a researcher, and the position of a community being researched – we need to consider who defines the research design, the decision-making processes being used, how the information is shared, and whose voices are being privileged and heard in the research itself.

Another definition is that “positionality refers to one’s location within a larger social formation, and thus affects how one experiences an environmental problem” (Pulido & Peña 1998). It relates to how our perspective and the way in which we relate to the world around us is heavily influenced by the society (and societal values) we live in and our own personal cultural influences.

We (Lucy and Izzy) first heard of ‘positionality’ in an Australian National University course on Indigenous Natural and Cultural Resource Management, where we were required to write a ‘positionality statement’ as an assignment. We were asked to reflect on our individual positionality relative to natural resource management. To do so, we had to reflect on a series of questions:

These are not easy questions to answer, especially when we are honest and critical with ourselves. It was an uncomfortable experience, as we were exploring sensitive social, cultural and political questions that naturally arise when living in a colonised nation. We have shared excerpts from our positionality statements so that we can demonstrate what we learnt through the process. We encourage you to read these and reflect on what your positionality statement might be.

Izzy

When writing my positionality statement, I thought about how I am accountable for maintaining my relationship with the environment, how I learn about the environment, and what connection to the environment means for me? I realised that throughout my life, there has been an emphasis on knowledge being taught within four walls, from books and online sources. Consequently, I had unconsciously structured my life to have nature ‘outside,’ where it is a place that I make time to go into, rather than being integral to my life. This means that I recognise the importance of nature in my life, but there is a degree of separation (wanted or not!) between myself and nature. As I reflected on this, I started to think about my situation in the context of what knowledge I value in natural resource management. For example, if I am used to learning about a place while not being there (like learning about the Great Barrier Reef at a university in Canberra), and in a formalised setting, it could follow that I have an unconscious bias to preference biophysical science as the knowledge I rely on when thinking about how to manage the Great Barrier Reef. This contrasts with relying on, or referring to knowledge that has come from experience, stories, or spiritual connection – in other words more personal and situated knowledge. It follows then, that when working with Indigenous Peoples I need to make a conscious effort to ensure I value and include all forms of knowledge.

Lucy

When writing my positionality statement, I began considering things in my past that shaped my understanding of the natural world. I reflected on my experiences of growing up in a rural area and my exposure to an array of western farming practices that were thought of as ‘best practice’. By exploring the lens of positionality, I have come to understand the natural world differently, and this has led me to question the utilitarian values we extract from the land, and how we have normalised exploitation of the environment in the name of economic growth. I realised that I had to ponder my understandings of ‘good’ and ‘bad’, rescoping the very notions underpinning my relationship with the natural world. My upbringing has undeniably shaped the way in which I view the world, and I have valued the introspection that has resulted in thinking about positionality. Although uncomfortable to think of things that can hinder embracing Indigenous Peoples perspectives, it’s a vital step to unpacking the continuing colonisation of education, academia, spaces, nations and groups within Australia. The multifaceted nature of environmental values have become much clearer to me, and I have started to question the inherent bias I would be bringing to my work, studies, and personal understandings of culture and society. I also began to enquire about alternative ways of relating through experiences and memories. I find that my interest has been peaked in natural and Indigenous land management, which values the environment holistically, looking at different ways of understanding the world around you.

As you can see, our positionality statements are quite different, but both attempt to tease out what aspects of our life may influence the way we interact with the environment. It shows how our positionality may hinder or make it difficult when working with Indigenous Peoples. By being aware of our positionality, we can begin to work through the internalised biases that appear in our day-to-day life and may impact on our work in natural resources management.

Recently at the ARRC, we have been developing a formal Reconciliation Action Plan which has acted as a catalyst for a shifting mindset within the organisation itself. The ARRC has always strived for a human-centred approach, hence our desire to act respectfully as non-Indigenous people in everything we do. This attitude sparked a discussion around positionality, revealing that the concept of positionality is relatively new for most people in the ARRC.

Izzy and Lucy, having the most experience of the topic, helped to inform the rest of the ARRC team as we realised that positionality must move beyond academia to become common in the workplace, especially considering our team aspires to centre people and relationships, instead of the ‘mechanics’ of river restoration.

Siwan, the Director of the ARRC, has a recent example where she started a speech at the Australian Freshwater Science Society conference with a positionality statement after giving an Acknowledgement of Country. She talked briefly about how her experience of the issue she was presenting on – communicating in Covid constrained times – may differ from an Indigenous Peoples perspective, and that is important for the audience to be aware of the biases present in the speech. This small act of reflection set the tone for the speech, as well as enabling the audience to listen with her positionality in mind, potentially prompting less bias on both an individual and group level.

This example made us see that we need to use positionality in our day-to-day operations within the workplace so that it becomes normalised. We also reflected that when interacting with controversial issues and topics, positionality may enable us to have more empathy for those of opposing views and remind us to consider multiple perspectives. When we don’t reflect on our positionality, power and privilege can ruin relationships by inadvertently silencing certain people in a conversation. This hinders efforts to build and maintain trust amongst those we wish to collaborate with. Positionality can help frame not only where we are coming from, but also help us understand that other people may be viewing the same issue from completely different backgrounds and perspectives. This awareness can lead to better outcomes in the river management space, and facilitate the engagement of more people, who may have previously been left out.

If you are interested in finding out more, here are a few resources to get you started on your own positionality journey.

Tanya Keed, a proud Aboriginal woman from Dunghutti Country, and Lori Gould who has worked with the ARRC for over twenty years, share how they have been working together to connect men and women who have been imprisoned, back to themselves, each other and to Country. We found this episode deeply emotional and also insightful, with Tanya’s story providing a window into the lived experience of an Aboriginal Australian. We feel deeply grateful and honoured that Tanya is sharing so much of herself and her story.

Lori Gould (left), Tanya Keed (right) and little Kayden (middle)