The wildlife recovery dilemma

Which species do we save?

Author: Kate McKenna

Which species do we save?

Author: Kate McKenna

Australia is facing a biodiversity crisis. Since 1788, according to the federal Environment and Biodiversity Protection Act, 39 of all mammal species (10%), 23 bird species, four frog species, one known fish species and 37 plant species are now extinct in Australia.

Native fish, in particular, are silently bearing the brunt of increasing degradation of Australian rivers, compounded by a changing climate and invasive species wreaking havoc on their habitats. In New South Wales alone, around 30 native freshwater fish species (917 threatened terrestrial and aquatic species in NSW in total) are considered threatened, along with countless populations facing localised extinctions. In 2020, a study found that 22 of Australia’s iconic small-bodied freshwater fish species have a high risk of extinction within the next twenty years if no changes are made in their management.

Deciding which species and populations receive prioritisation and funding can be a difficult emotional and moral question; why should we save one species over another?

Biodiversity conservation is critical to protecting native species from becoming further endangered. Recovery projects and their funding are important, however, not all threatened species can be protected at once. Water and fish managers face the challenges of limited funding and resources, amidst a huge number of species and populations that need recovery projects; but how do they make these difficult decisions about which species get these resources?

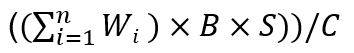

To make the process of choosing species for conservation a less daunting and emotionally-charged task, in 2009 a group of researchers in New Zealand designed a method to prioritise wildlife recovery projects called the ‘Project Prioritisation Protocol’ (PPP). The method ranks species conservation projects based off several key aspects, mainly through a ‘benefit:cost’ ratio:

The PPP is then calculated with a formula that gives the different conservation projects a ranking. It looks complicated, but once broken down, it’s a useful tool:

The PPP gives cultural and biodiversity values the same weighting in the equation. For a conservationist, who sees a species’ biodiversity value as a more important factor in conservation, this may not make sense but in reality, both values are important.

Projects that have a higher cultural value (e.g. protecting well-known threatened species like Koalas or Platypus, or species that are have important values for Indigenous peoples) are more likely to have greater community interest and engagement, which may lead to more funding, resources or volunteers to support the project.

On the other hand, species with higher biodiversity values are just as important but may interest fewer members of the general community. Threatened species, like the Southern Purple-spotted gudgeon or the River blackfish, play an essential role in ecosystems and also need to be protected.

This is why the PPP is a useful tool to fairly weigh these different aspects of a recovery project, and to ensure species with high biodiversity value or cultural value are equally recognised.

The PPP has been implemented in various jurisdictions, such as New Zealand and New South Wales. In New South Wales, the model is used to support the Save our Species program.

Similarly, the ‘Open Standard for the Practice of Conservation’ is another example of an approach to prioritising conservation projects that considers the project’s ecological, social, political and cultural context. This approach is implemented worldwide and locally by Bush Heritage in NSW.

In the Upper Murrumbidgee of NSW, the Native Fish Recovery Strategy has focussed its recovery actions on local fish populations that are small yet resilient species. The works undertaken to conserve these species also often have broader benefits for the ecosystem and other threatened species.

The works focus on a coordinated and strategic approach to reduce threats and improve habitat to support species recovery along the upper Murrumbidgee River between Tantangara and Burrinjuck Dams. This includes protection of high quality habitat by riparian weed control and mitigating erosion, as well as connecting and restoring habitat via revegetation, stabilising instream sediment and installing additional instream habitat. Genetic rescue of Macquarie perch via fish stocking, better management of flows, improving water quality, reducing impacts of recreational use and fostering community engagement and stewardship also assist species recovery as well as support the health of the upper Murrumbidgee which is the major waterway enjoyed by the community of our nation’s capital city.

The success of recovering these resilient species and habitat raises the question of whether we should focus on recovering species that have a higher likelihood of successful recovery or whether we focus on species that may need more resources and work as they are more endangered but may not be successful – this is where conservation tools like the PPP or the Open Standard method are useful.

The PPP can be used to facilitate discussions about threatened species conservation between people. Conservationists need more conversations and resourcing to share their work and build off the success of different projects. The PPP shows that we need more funding and resourcing to be placed into these discussions and frameworks, as well as the species that need protecting. The PPP and the Open Standard method can be used at local, regional and national scales of biodiversity conservation projects, and in different organisations and institutions, including government bodies and NGOs.

The PPP harnesses the emotion that many people feel about protecting species from extinction and can be used to bring them together to have the best outcome for biodiversity. By ranking and measuring the possible outcomes and success for the specific species and projects, the PPP shows the ‘whole picture’. It enables scientists to not only support a single species that they may care deeply about but also see which other species need critical funding and support.

Conservation projects rely on the hard work of people who are passionate about protecting our wildlife from becoming extinct. Their work can be supported by the PPP as a tool to ensure funding is shared between projects that are the most likely to successfully protect and recover Australia’s biodiversity in the fairest way possible.

Featured photo: The Southern purple-spotted gudgeon is a threatened freshwater fish species found in south-east Australia. Source: Gunther Schmida.

This article was originally published at: https://finterest.com.au/the-wildlife-recovery-dilemma/