It is sometimes assumed that providing flows of any magnitude, velocity, rate and frequency will benefit fish, however, as Kat Cheshire and Anthony Townsend explain, we need to provide a range of flows to meet different fish needs.

There are 46 native fish species in the Murray-Darling Basin (MDB). Each of these species has evolved differently, over millennia to the boom and bust nature of the Australian riverine landscape. Water and fish go together, and different fish have adapted diverse life cycles in response to the varying flow conditions (i.e. floods and droughts) of the Basin. When we look at the fish species in the MDB there are some basic differences in life cycle strategies:

- some are dependent on intermittent high flow pulses to spawn,

- others require fast flowing riverine habitats to live in,

- some require the inundated wetlands on our floodplains, and

- others can complete their life cycle in almost any conditions, including low flows.

Due to their dependence on different flows, our native fish populations are suffering from changes in the system. These changes occurred over just a handful of decades as a result of water extraction and river regulation. Fish play a critical role in the whole river system by cycling nutrients, providing food for other parts of the food web like waterbirds, and sustaining a billion dollar a year recreational fishing industry. Looking after fish, therefore, provides a range of environmental, social and economic benefits.

We know that restoring fish populations through smarter water delivery and protection of natural flows can be an effective way to manage river health in many ways:

- Improves completion of native fish cycles, which have adapted to the natural boom and bust of the MDB System, including providing cues for some fish to spawn (eg. Golden perch)

- Maintains water quality for fish health, including levels of dissolved oxygen, salinity and temperature.

- Ensures access to a diversity of habitats (wetlands, flowing water, river channels, drought refuges) during dry times, and nesting sites (woody debris, aquatic vegetation, gravel or cobbles).

- Water that inundates river benches and floodplains provides food for adult and baby fish, helping maintain their condition. Health fish are more likely to spawn, move and respond to difference cues, increasing their survival potential.

- Supports lateral and longitudinal movement of fish throughout the MDB (eg. Murray cod and Silver perch have been recorded moving hundreds to thousands of kilometres), ensuring genetic diversity of fish and allowing dispersal to different locations.

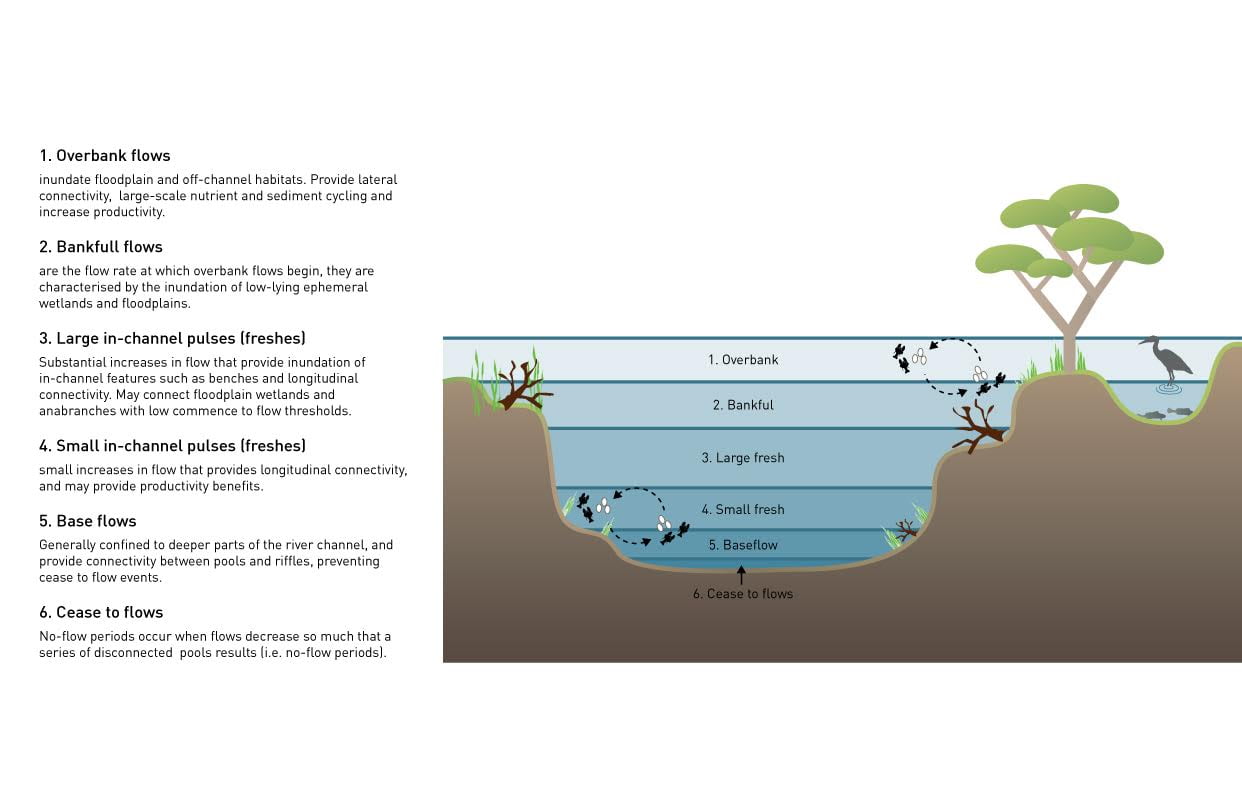

Figure 1 below shows the range of different flows our rivers and connected wetland floodplains experience. Fish respond differently to different flows, and this means that assuming any water will have positive outcomes for all fish is too simplistic.

Figure 1: River and wetland/floodplain flow descriptions – different fish need different flows. Figure NSW DPI Fisheries, for better quality image download the pdf of this article – the link is at the bottom of the page.

It is not feasible to manage water delivery specifically for each of the 46 different fish species in the MDB, but our team did want to manage water more effectively so that we optimised outcomes for fish. Our response to this problem was to develop and approach using ‘functional groups’, where we sorted the fish into groups based on shared life history and characteristics and responses to flow.

NSW DPI Fisheries, in collaboration with fish scientists and managers from across the Basin, used these functional groups to develop a simplified management framework for fish and water management called the ‘Fish and Flows’ projects. We built on previous functional group approaches for fish and integrated the latest science and knowledge about flow related responses and life history requirements of fish. This enabled us to develop different functional groups of species for the southern and northern Basin.

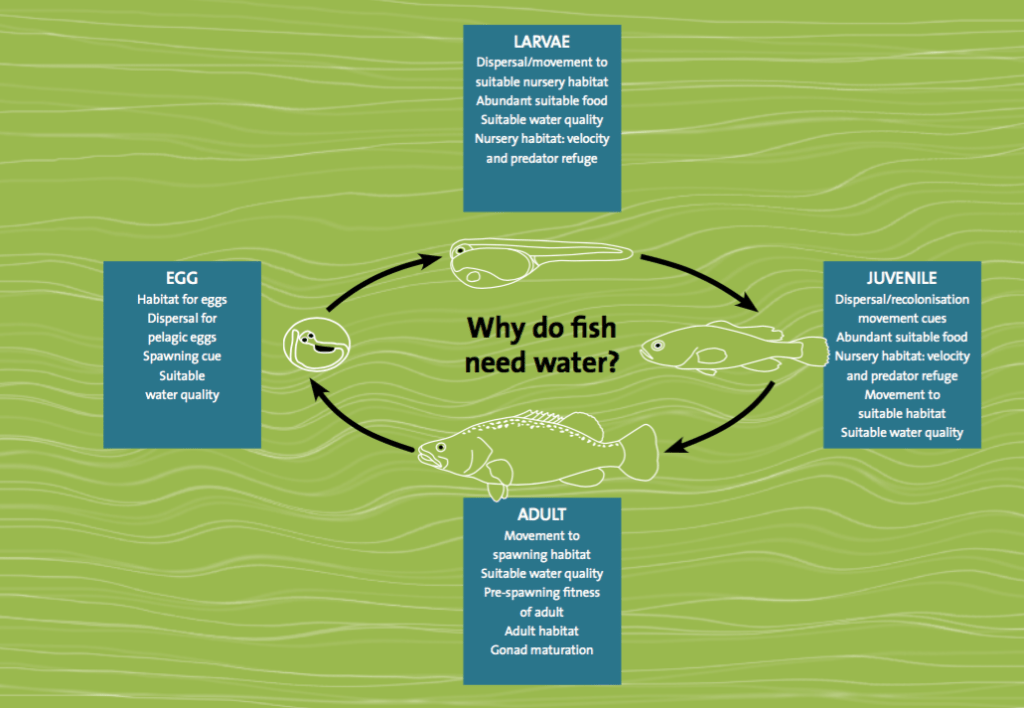

These projects focused on how water and flow influence key characteristics of fish life cycles (see Figure 2), with key stages being:

- egg, larval and habitat preferences,

- distances of juvenile and adult movements,

- if cues are required to initiate spawning,

- how and where they spawn (e.g. nesting or not),

- how many eggs they produce,

- how frequently they need to spawn to maintain populations,

- life span, and

- survival and maintenance of populations (dependent on food availability and water quality requirements).

Using these characteristics we identified five different functional fish groups that are now being used to simplify water management targets for fish (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Functional groups of fish developed during the Fish and Flows projects, highlighting their flow-related attributes and example species. A better quality image of this can be seen on the downloadable pdf which is at the end of this article.

These groups of fish all rely on water and flows, but respond differently to various parts of the flow regime (see featured image). We want to improve our understanding of how the magnitude (both volume and height), frequency and duration of different flow events influence each group. This will allow water management strategies to be fine-tuned over time to achieve outcomes for specific functional groups.

In addition, we want to discover the thresholds required to maintain populations during drier times. We hope this understanding will enable us to improve their condition during wetter periods and refine our capacity to achieve outcomes under various water management scenarios.

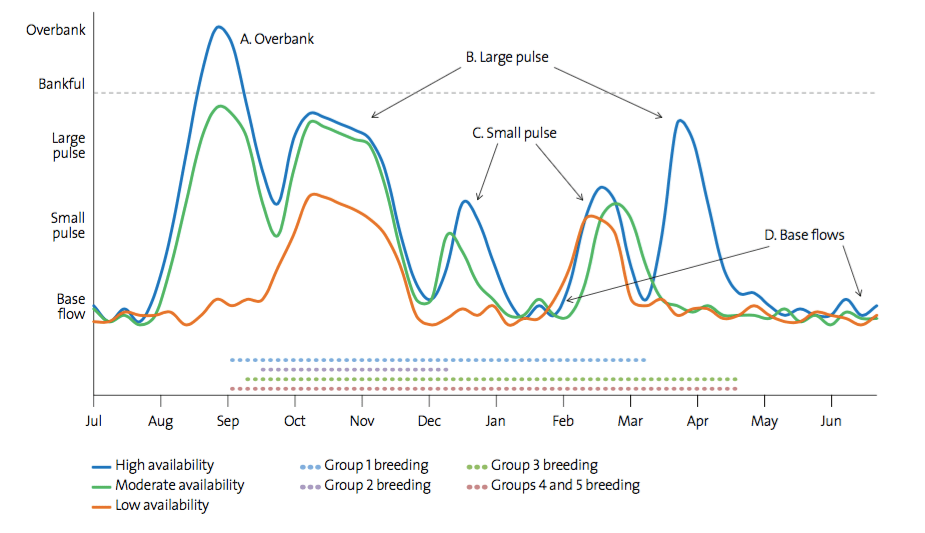

As part of the ‘Fish and Flows’ projects, conceptual hydrography were developed. These describe specific elements of flows needed to support he spawning, recruitment, maintenance and condition needs of each of the fish functional groups (Figure 4). Fish have adapted to historical flow patterns, so the hydrography consider the natural variation in flow magnitude, seasonal timing, and duration for a system. It is expected thatches generic hydrography will be adjusted by water managers to suit different locations across the Basin in the design and prioritisation of watering actions.

Figure 4. Conceptual flow hydrography for three water availability scenarios (high, moderate and low) and breeding season windows for each functional group of southern MDB fishes (dotted lines) that are shown in Figure 2.

While water is the most important element to keep fish alive, fish cannot live on flows alone. We can achieve greater outcomes from environmental water by undertaking parallel complementary actions including: improving fish habitat through re-snagging, restoring in stream and riverbank revegetation, fixing fish passage, screening pumps and diversions, and controlling invasive species. Flow management and complementary actions working in parallel will support bringing native fish back into a healthy working Basin, and will increase the potential to achieve long-term social and environmental outcomes through water management.

To read this and other great stories like it, you can purchase or download a copy of RipRap 39 magazine. A pdf version of Katherine and Anthony’s story is also available to download here.