Geoff Vietz and Steve Clarke from Streamology, highlight the need for us to turn our attention to our urban waterways where the majority of our population live, work and play…

In the Australian waterway industry, we tend to focus on our rural waterways for river protection, rehabilitation and restoration, but if we are serious about connecting people with healthy rivers, then Australia’s urban settings should be our focus. It is near urban waterways that the majority of our population reside, yet these waterways are significantly degraded by the effects of landuse. The problem is that conventional drainage has the objective of sending rainfall from urban catchments as quickly as possible to the waterway. Yet in a drying climate don’t we want to retain water in cities? If so, then we need to better link urbanisation to streamflow changes and the social, ecological and physical values of waterways. By doing this we may address waterway condition and water supply in urban catchments.

- Minor flooding around a partly blocked storm drain in an urban street.

- Constructed wetland in Melbourne making smarter use of stormwater.

So what is the problem?

The overwhelming majority of the world’s urban areas are located near water, and this is because water plays a critical role in the livability of cities and towns. From the water we drink, to the green spaces we are drawn to, and to the outlets for our wastewater and stormwater, rivers and streams are the lifeline of human settlement. Knowing how attracted and dependent upon water we are, it’s not that surprising that those very same streams we rely upon for social and environmental benefits, suffer greatly due to the effects of urbanization.

In a drying climate, it is perhaps a surprisingly cruel twist of fate that those impacts are primarily due to urban streams and rivers having too much water from increased stormwater runoff and wastewater treatment plant outflows. By all indications, this is going to get worse, with 70% of the world’s population projected to be living in urban areas by 2050. That’s a sobering number on a global scale but, in Australia, more than 90% of the country’s population already live in urban regions – with Australian cities experiencing a nominal growth rate of 1.6% per year. This change from paddocks to urban suburb, and the associated increase in impervious area and stormwater drainage connections, can lead to more than 10 times the volume of stormwater runoff.

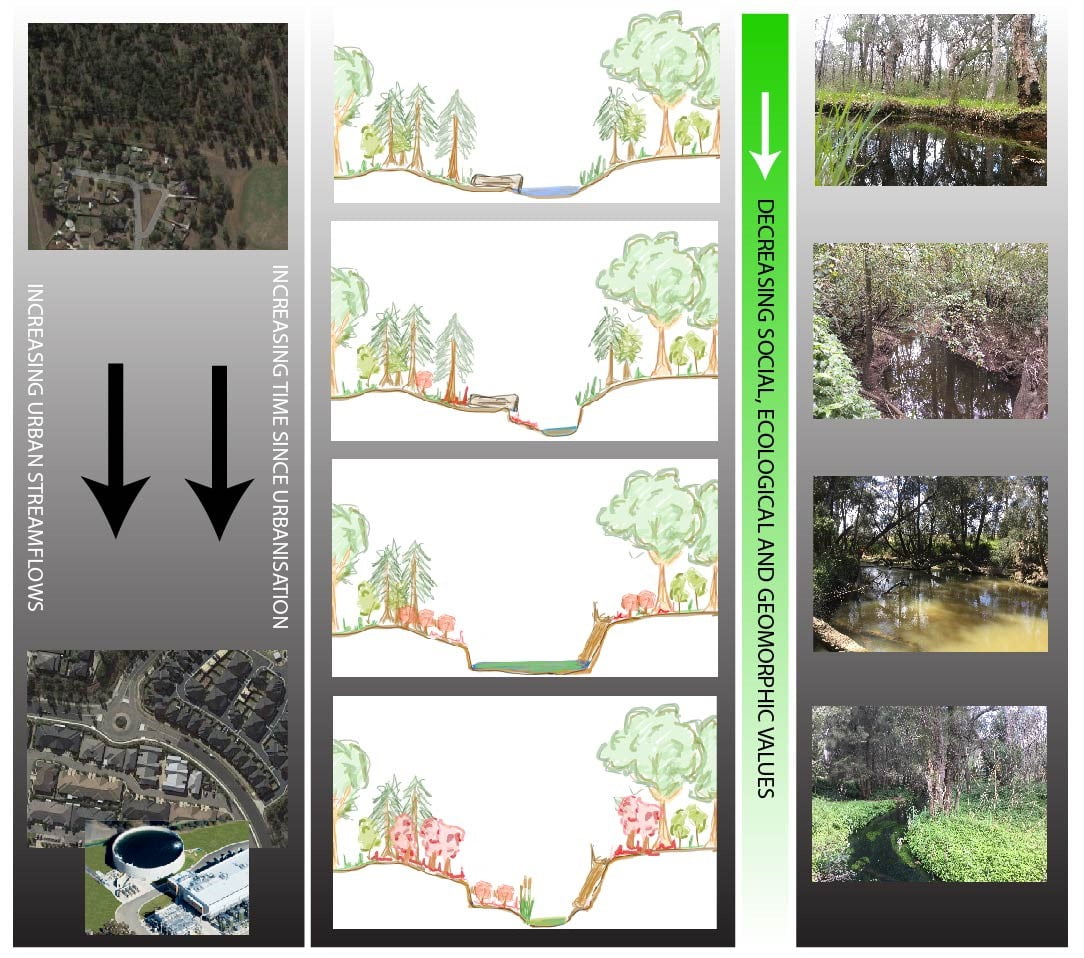

These sweeping increases in runoff have dramatic consequences on the values of our waterways, and the unnatural pattern of those runoff flows only makes things worse. In Figure 1 we can see how urbanisation impacts on our waterways and steadily decreases their social and environmental values.

Typical changes to receiving waterways under catchment urbanisation (sketches by Carl Tippler).

When looking at the changes in these waterways, it is the channel morphology (shape) that is the most striking, with waterways being incised or enlarged, making them difficult to restore without significant resources and often some big machinery! They are places we do, however, need to focus our attention as there is increasing demand for water supply in cities. In Melbourne during an average year (650mm rainfall), 608 GL of stormwater is generated on roofs and roads (equal to more than 300,000 litres per home per year). In simple hydrologic terms: if too much runs off we don’t have enough to supply our needs. It follows then that by investing in our urban waterways we may be able to alter the timing and pattern of flows so that we can retain the runoff and meet supply requirements.

Why aren’t we then jumping in? Well, a number of questions must be addressed:

- What is the financial cost of addressing the stormwater problem?

- What are the water supply and landscape benefits?

- How much water must be captured and how would this be released?

- How much water storage and use is required?

To answer these questions requires us to make an explicit link between the development options for addressing urban stormwater runoff in the catchment (including outflows from wastewater treatment plants), and the values we wish to retain for waterways – social, ecological and physical.

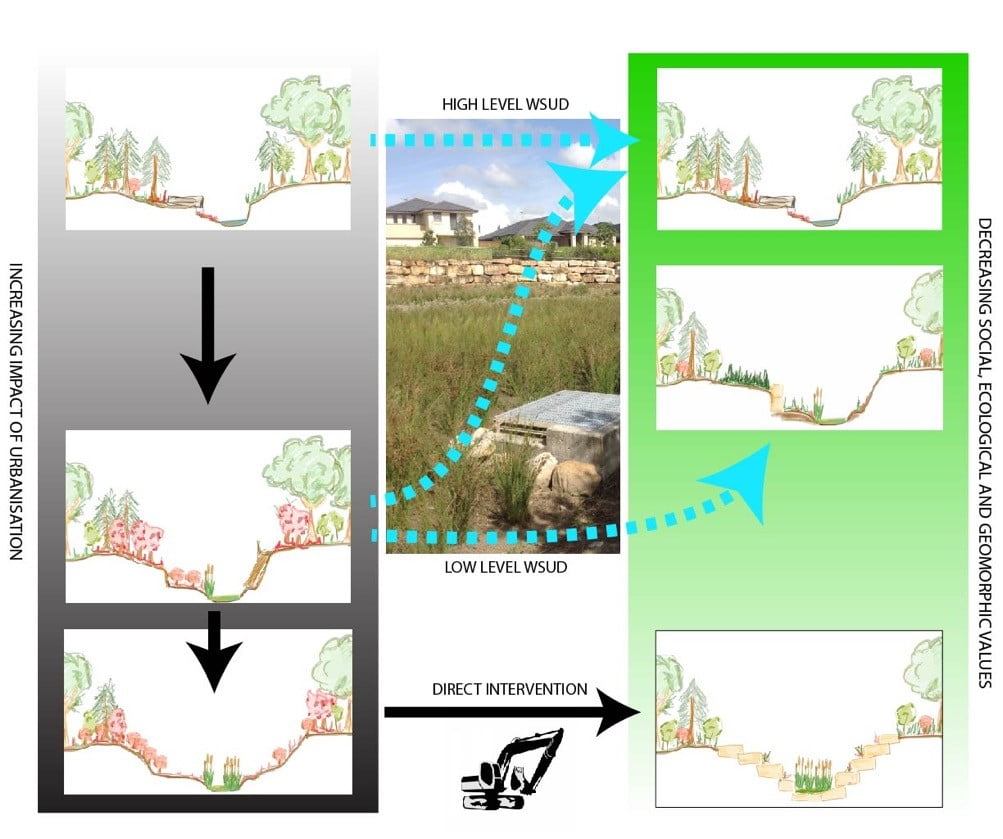

We know that social values can often eventually lead to recognition of ecosystem values for waterways in cities and suburbs. It is these imperatives for linking these social values to urban planning scenarios that led to the development of the Urban Streamflow Impact Assessment (USIA). USIA identifies the streamflow changes that are as a result of catchment urbanisation and are known to impact waterway values. The USIA draws upon nine specific hydrologic metrics that include, for example, baseflows, disturbance events and floodplain inundation. These metrics are explicitly linked to the waterway values identified for the stream: social, ecological and physical, with community workshops used to determine what these specific values are for different locations. In addition to the workshops, field assessments of ecological and geomorphic characteristics and desktop linking of hydrology to these values through hydraulic modelling are used to complete the USIA process. The USIA then enables decisions to be made about possible waterway management interventions to enable values to be retained, but also the hydrologic functioning to be optimised to meet both supply and demand. Figure 2 shows the point of intervention following the use of a USIA process.

WSUD – Water Sensitive Urban Design. (sketches by Carl Tippler)

The USIA approach has been applied to case studies in the South Creek catchment of western Sydney, which is undergoing some of Australia’s most rapid rates of urbanisation and, as a result, significant potential to impact on waterway form and condition. As the image below shows, for this part of Sydney there is explicit recognition of the connection between liveability and waterway health.

Technical credentials

The USIA approach has strong technical underpinnings, with the different metrics enabling a target for levels of planning and development options. For example, even if three quantitative metrics are identified as a target for a particular waterway, then hydrologic modelling (using a platform like e-Water Source or MUSIC) can be used to optimise Water Sensitive Urban Design (WSUD) measures that facilitate those hydrologic targets. This enables creativity in stormwater control measures and patterns of operations from Waste Water Treatment Plants that were previously not easily quantified. Ultimately, the method identifies ‘what is lost’ if planning or development controls are not met under Business As Usual, what can be retained or returned, and how much effort is required. The USIA method will help inform the business case for waterway protection and the extent of WSUD to be implemented in our suburbs and cities of the future.

The effort to capture and use stormwater, or recycled water is by no means an easy task. Yet, neither is trying to recreate nature, or the social values lost. At least tangible examples of WSUD benefiting receiving waterways are now available (see the Little Stringybark Creek case study). New developments (greenfield sites) provide the greatest potential for application of capture, storage and use and we believe this needs to be set up early in the process of the development cycle.

What are we waiting for?

It is eight years since the release of the Australian governments’ ‘Our Cities, Our Future’. In this document were the two relevant priorities: securing urban water supply, and protecting and enhancing natural ecosystems, waterways and biodiversity. We are closer to recognising the link, but the impetus and options to make the change still appear to be on a slow burn. This is frustrating because the benefits of water being retained in the landscape include greener spaces, improved vegetation, and healthier water bodies, all of which help to mitigate the urban ‘heat island’ effect, leading to improved human thermal comfort. Of course, greater accessibility to streams also provides natural settings for ambling and reflecting, in otherwise hectic environments, all of which contributes to improved livability for urban and suburban dwellers.

Not somewhere a person might wander, but with flows those rocks will provide resting places for fish moving up and down the river. This is alongside the Lane Cove Tunnel in Sydney. Image from http://www.kistudio.com.au/project/lane-cove-tunnel-wsud/

If our generation is leaving one unfortunate legacy it is the physical and mental disconnection from nature. Urbanisation is a rapidly accelerating vehicle driving this concern. This human disconnection will mean our future community will be poorly experienced in considering the value of healthy waterways in the Australian landscape. So, if we would like to see this future community recognise the values of waterways we need to identify what can be done to retain them. Hopefully this means we will see children in the suburbs and cities playing around our healthy future streams, or even in them. In doing so we may be creating a community aware of the value of waterways, whilst contributing to water supplies for a growing population.

These are the opportunities we want to create for our communites – connection to nature. Photo Geoff Vietz

More information on this topic can be found on the Streamology website by following this link to their published works.

Acknowledgements

The information in this article is drawn from too many to reference here. The USIA method is the result of a significant collaborative approach and was developed by Streamology and CTEnvironmental with Sydney Water. It draws upon research undertaken by the Waterway Ecosystem Research Group at Melbourne University, the Melbourne Waterway Research-Practice Partnership, with Melbourne Water, and the CRC for Water Sensitive Cities. More information on USIA can be found on the Streamology geomorphic investigations and assessments webpage.

Dr Geoff Vietz is the Director of Streamology, a niche consulting company focused on bridging the divide between the science and practice of waterways, seeking strategic solutions for our current and future water and waterway challenges. Geoff is also a Senior Research Fellow in the Waterway Ecosystem Research Group at the University of Melbourne, which is currently working on urban water and waterway challenges with the Melbourne Waterway Research-Practice Partnership. Steve Clarke is a hydrologist and waterway specialist with Streamology, and is currently involved in the application of the USIA method. Most importantly, Geoff and Steve have a passion to see healthy rivers, no matter the landscape context, they can also link you to a lot more references if you want to know more.

- Geoff

- Steve

Geoff can be reached via the following contact – geoff@streamology.com.au / 0421 902 970

Visit our Resource Centre

We have been working for many years to turn science and experience into useful communication resources organised against key river management issues. These resources provide you with the opportunity to explore a range of topics and can be found here.

GO TO RESOURCE CENTRE