Changing the way we view our rivers

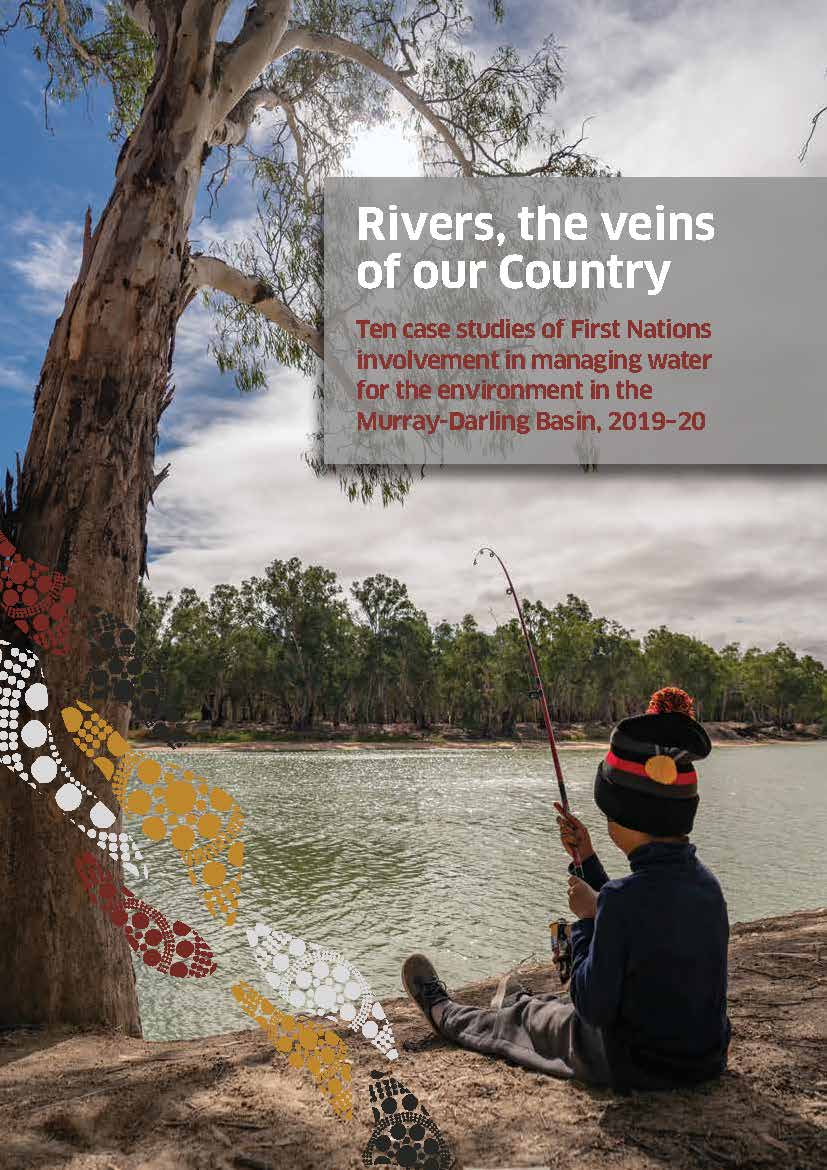

The way we view our rivers and water also shapes their ownership and use. Looking at recent publications from Indigenous perspectives on the environment, the difference between Western perspectives on nature and water as resources to be harnessed, and Indigenous perspectives about rivers being part of the living landscape, are evident. Some examples of these stories are captured in Rivers, the Veins of our Country. They focus on the idea that “if we look after it, it will look after us”. In contrast, western perspectives often imply the idea of controlling and exploiting water.

In recent times, Western ideals have been reimagined through the Rights of Nature movement, which rejects the notion that nature is human property. The manifest of this movement is that the highest legal protection needs to be for ecological health, as human beings are just one part of the larger, interconnected web of life, completely interdependent on the rest of the natural world.

The Rights of Nature movement has been used to grant legal personhood to nature with examples in Aotearoa (New Zealand), where three key environmental features now have legal personhood: Te Urewera National Park, the Whanganui River, and Mt. Taranaki. The rights of nature in New Zealand aims to use traditional knowledge and ways of understanding the environment and its ownership, which stems from the Māori idea that the environment has living spirits.

There are criticisms of the Rights of Nature movement’s use and relevance in Australia, notably from Dr Virginia Marshall, who explains that it further reduces the rights of Indigenous peoples, and outrightly removes their ownership of the land that their ancestors have been living on for 60,000 to 80,000 years. This is because the approach legally separates Indigenous communities from caring for Country and acts as another colonial tool to remove Aboriginal peoples’ inherent rights and interests, perpetuating an ongoing cycle of further disempowerment for Indigenous nations.

There are however potential benefits from recognising our rivers as legal entities in that they can then have a right to exist, be healthy and to flow. In some examples around the world, while the river has been given legal personhood status, it does not include the water within its banks, leaving the river unable to have its flow requirements met (see work by Dr Erin O’Donnell for further discussion). This adds another complexity to the issue, but having the conversations about legal personhood for rivers, at the very least, may start to change the way we view our waterways.

This complicated issue demonstrates the need for further reform of environmental policy, not only in Australia at a state and national level, but also globally. Indigenous populations around the world are disempowered by legal frameworks which restrict their ability to exercise their custodianship of their land and water. It is likely that without grassroots and participatory implementation of rights of nature, in an Australian context, the Rights of Nature framework would not be effective in supporting Indigenous ownership of nature.

Written by Kate McKenna and Andy Lowes

Written by Kate McKenna and Andy Lowes